by Tim McMahan, Lazy-i.com

Today is the 10-year anniversary of the opening of The Slowdown.

The club’s public inaugural show, Friday, June 8, featured Little Brazil, Domestica, Art in Manila, Now, Archimedes!, Flowers Forever and Cap Gun Coup. Neva Dinova headlined the Saturday, June 9 show, with Bear Country, Ladyfinger, The Terminals and Mal Madrigal. Ah, those were the days.

To mark the occasion — and to properly recognize the 10-year anniversary of The Waiting Room’s opening — I wrote the following article for The Reader that talks about the clubs’ origins and how they’ve managed to not only survive, but thrive, 10 years later. Maybe we should have done this story in March when The Waiting Room hosted a month-long celebration, because The Slowdown is doing nothing publicly to mark the occasion. Oh well.

You can also read this read this in print in the latest issue of The Reader, on newsstands now or at The Reader website, but you’d miss out on all my sweet photos…

Ten Years Gone

Over the course of a decade, venues The Slowdown and The Waiting Room have transformed Omaha’s live music scene.

By Tim McMahan

Try to remember the way it was before The Slowdown and The Waiting Room opened 10 years ago.

Your choices for seeing an indie rock show were limited to Sokol Underground, the dark, smoky (remember, you could still smoke in clubs back then) basement of Sokol Auditorium located on South 13th Street. While somewhat large (its capacity was at least 400), the room felt strangely claustrophobic, with sight lines marred by metal support poles strategically placed in the most inopportune places. And while there was a decidedly punk-rock/DIY feel to the joint — and a surprisingly good sound system — Sokol Underground always felt temporary.

It didn’t stand alone. Shows also were hosted at The 49’r, O’Leaver’s, Mick’s and the odd west-Omaha bar, house or hall that splurged on a PA. BY 2007, rock destinations, like the all-ages punk club The Cog Factory and everyone’s favorite bowling alley, The Ranch Bowl, were long gone.

But folks in the scene knew things would change. They had to. In 2007, Omaha was still basking in the afterglow of national notoriety for its indie music scene, thanks in large part to One Percent Productions, who had a rep for booking the best touring indie acts, and Saddle Creek Records, home of indie superstars Bright Eyes, The Faint and Cursive (among others).

For Omaha to take that next step, it needed a first-class music venue (or two) for bands to show their stuff.

The Waiting Room, located in the heart of Benson, was the first to open in March 2007. The Slowdown, located in the yet-to-be-established North Downtown area, would follow in June of the same year. The clubs would grow to become focal points of their respective business districts, revitalizing the areas. But it didn’t happen over night.

Robb Nansel, left, and Jason Kulbel in front of The Slowdown, circa 2007.

The Slowdown

Jason Kulbel and Robb Nansel were more known for their record label — Saddle Creek Records — than their experience running music venues or promoting rock shows, though both had booked a handful of notable shows at Sokol Underground in the early part of the 2000s.

In 2005, Saddle Creek was enjoying what arguably was the height of its national fame, and likely the peak of its revenues, as all three of its crown jewels — Bright Eyes, Cursive and The Faint — were producing the best albums of their careers. For years, Kulbel and Nansel had a shared vision for opening their own music venue, but it was Kulbel who had been lured back from California in 2000 solely for the purpose.

“There was a hole in Omaha,” Kulbel said during an interview on the patio of The Trap Room, a tiny bar also owned by the duo that sits next to The Slowdown. “We’d been to countless good clubs in other cities, some cities a lot (smaller) than Omaha, population-wise. It just seemed like something that could do well here.”

Kulbel said they hoped a club would help keep people from relocating. “That was an early motivation, for sure,” he said. “A lot of people moved away, myself included, trying to find greener pastures or better places.”

It would take years just to find the right location. Among those considered and discarded was an old creamery at 14th and Jones streets, a big, open room with lots of potential. Unfortunately, they couldn’t get the owners to sell. “We were ‘full steam ahead,'” Kulbel said. “The guys that owned it just decided we looked too young, though we were in our 30s. It was too hair-brained an idea for their tastes.”

The old Magic Theater on South 16th Street also was considered “pretty heavily,” Kulbel said. But by 2004, he and Nansel had gathered enough seed money from Saddle Creek’s success that they decided to build rather than renovate an older building. Their first location choice was a small commercial district just west of Radial Highway along North Saddle Creek Road, next to one of Omaha’s most iconic bars, The Homy Inn.

They acquired purchasing agreements for property where two car washes stood, but before they went through with the purchase, decided to announce their plans to the neighborhood. And that’s when all hell broke loose. A neighborhood meeting held in November 2004 was “a true nightmare,” Kulbel said. “The first woman that we called on for questions started crying. And it all went downhill from there.”

It would be Omaha City Councilman Dan Welch, who knew the neighborhood would never support them, that convinced Kulbel and Nansel to look elsewhere. He introduced them to City Planner Bob Peters who pointed out the property where The Slowdown now resides, an area just north of downtown Omaha.

Construction begins at The Slowdown complex, Sept. 25, 2006.

“There was nothing there at the time,” Kulbel said. “Everything was vacant. After you just went to war with a neighborhood, the most appealing thing is that there are no neighbors.”

It was Todd Heistand of NuStyle Development, who was redeveloping the nearby Tip-Top Building, that convinced the duo to build more than just a club and headquarters for their record label. Rachel Jacobsen, the genius behind Film Streams, came on board next.

With a sizable loan and some attractive tax incentives, Kulbel and Nansel bought the land from the city and began laying out their plans for their dream club.

“We cut no corner,” Kulbel said. “The way the venue functions, the way the stage is, the sound system, the balcony, we never swayed from our vision one bit. Anything built was because we thought that’s exactly how it should be built.”

About a year and a half after buying the land, The Slowdown opened on June 8, 2007.

With a capacity of around 700, The Slowdown’s large stage was always destined to be the club’s center point, but it’s the smaller front room, with a capacity of only a couple hundred, that has hosted the most shows. “The front room has worked out really well for smaller shows, which I didn’t envision in the beginning,” Kulbel said. “It was made to be way more of a bar than a show room.”

Of the roughly 150 events booked at The Slowdown each year, Kulbel said probably two-thirds are booked in the front room.

Kulbel said financially, the club’s early years were thin. “There were times in 2008 through 2010 when we were taking out loans to make payroll,” he said.

When the club first opened, Kulbel and Nansel had intended to book the kind of indie bands that historically had played at Sokol Underground. “That dream died rather quickly,” Kulbel said. “You figure out that it’s a business, and you begin going back to the people that you have to take care of and the staff that you have to pay. You’ve got to have a good steady volume of shows and people coming through the door.”

As a result, the Slowdown began to broaden the style of music it booked. That fact played into the three milestone events over the life of the club that Kulbel said radically changed his views of how the Slowdown was run.

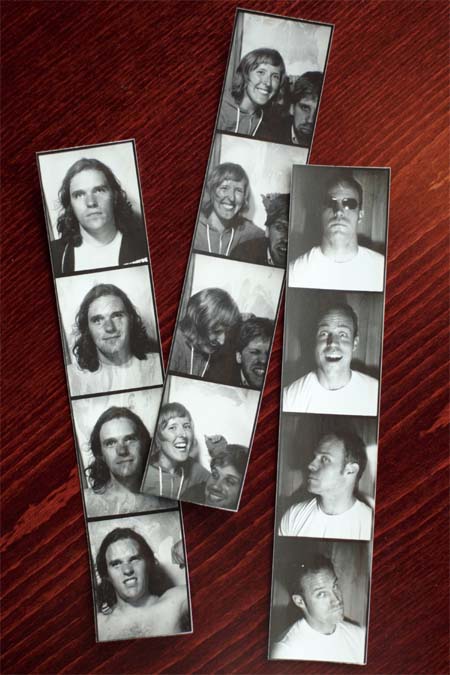

The 2007 staff, from left, Slowdown sound engineer Dan Brennan, hospitality/event coordinator Val Nelson and bar manager Ryan Palmer.

The first milestone was losing the club’s “hospitality director” Val Nelson in February 2014. “Our technical title was ‘hospitality,’ but she ran the venue,” Kulbel said. “She was the point person for all the staff. She was basically the general manager.”

In addition to doing hospitality, Nelson, who had moved from Kalamazoo, Michigan, to take the job, also handled the club’s back office and dabbled in bookings. When she left Slowdown, Kulbel immediately took over her responsibilities, which he wasn’t ready for.

“I don’t think I’ve ever felt a weight like that. I didn’t know what to do,” Kulbel said, adding that the departure was so swift, he never had a chance to ask Nelson how things worked. “I had to figure out how to do everything that she did. It was a really rough few months; truly awful.”

But the trial by fire ended up being the best thing that could have happened to Kulbel. “It taught me a lot about the business that I own and run,” he said. It wasn’t until July of that year and after struggling through his first College World Series season without Nelson that Kulbel finally began getting his sea legs. “I felt so much better about everything because now I knew how it all worked.”

The second milestone was the shooting that took place Halloween night 2015. According to published reports, 28-year-old Jamar Fields was shot and killed inside the back door of The Slowdown after a brawl.

“It didn’t really change how we do business, but it changed some of the people that we do business with, and it just really changed my life,” Kulbel said. “It was devastating for me, for my wife and family and everything.”

The club closed for a few days following the incident. When it reopened, Kulbel said for the first few weeks, “you could cut the tension in the room.” Patrons returned to shows, but the possible after-effects of the incident didn’t hit Kulbel until he received a call from the mother of a bride who had planned to host a wedding reception at The Slowdown the following summer.

“She said she was nervous because they weren’t sure we’d still be open in July,” Kulbel said. “It just absolutely floored me because that had never crossed my mind, that one idiot could walk into your club and tear it all down with one stupid thing.”

Unfounded rumors of Slowdown’s possible demise due to lawsuits or the club’s perceived inability to acquire insurance rattled through the scene. But less than two years later, the incident is behind them.

The final of the three milestone was Slowdown’s decision in January of this year to sign a deal with Knitting Factory Entertainment to take over the lion’s share of the club’s booking.

“I’m 43, so I listen to less music, I go to less shows, I just don’t really have the best pulse on that sort of thing,” Kulbel said. “We talked to Knitting Factory for probably nine months before we actually had a deal with them. I had been been curating a lot of shows and there were pretty big misses just because I don’t do it for a living. I can run the club, I can run the property, but when I’ve got to really sit down and pick out what to do for a calendar or even pick out what to book locally, I’m not the best judge.”

Kulbel said Slowdown’s relationship with Knitting Factory goes beyond booking. “They can answer questions about anything that I can throw at them,” he said, “from the type of cash register to use to how many shows we should be booking a month and everything in between.”

The new relationship also frees up Kulbel to focus on he and Nansel’s real estate holdings. Their tenants include Blue Line Coffee, Urban Outfitters, Hook and Lime, Trap Room, Slowdown and the recently opened Zipline Brewery in the space that used to house Saddle Creek Records’ warehouse.

The Slowdown days before opening in 2007.

“Owning our own building and the surrounding real estate helps a ton,” Kulbel said. “It’s not to the point anymore where Slowdown borrows from the property, but it was in the past. There were times when Saddle Creek floated the property, and times when Slowdown floated Saddle Creek. I think everything now has set sail and looks pretty good, but the property is the future. I don’t have a retirement account, and I wouldn’t consider Slowdown to be my retirement account. It’s the property and the buildings.”

Today, the once vacant lots that surround their property are now filled with hotels, apartments, restaurants and the massive TD Ameritrade Park, home of the NCAA Men’s College World Series.

If you wonder why Nansel isn’t quoted in this article, it’s because he currently lives in Los Angeles, where Saddle Creek Records has additional label operations. A little over three years ago Kulbel separated himself from label operations, which is Nansel’s full-time focus. Why the split?

‘It just became a drag once the club opened and the property was a concern as well,” Kulbel said. “For years I had three full-time jobs — the property, Slowdown and Saddle Creek. Then three years ago my wife and I had a little girl to join my two step-kids, and something had to give.”

Slowdown was always Kulbel’s labor of love. “It’s mine and Robb’s thing, but it was always way more of my thing and the label was way more Robb’s thing.”

Though neither are involved in the other’s day-to-day operations, the two touch base every Tuesday via phone, though Kulbel says he knows more about what’s happening at the label from talking to Omaha-based Saddle Creek personnel, who still have offices above Slowdown.

For Nansel, the challenge for Slowdown’s next decade is staying relevant and staying open. He now knows that an unexpected catastrophe could spell the end. Still, “I think the club business is a good thing to be in,” he said. “I think people are always going to want to go to shows and have a couple drinks and go home. If you were going to place your bets on a portion of the music industry, I think running a club is a pretty safe place to bet.

“I hope The Slowdown is open 30, 40, 50 years from now. That would be fantastic, but it’s really hard to say.”

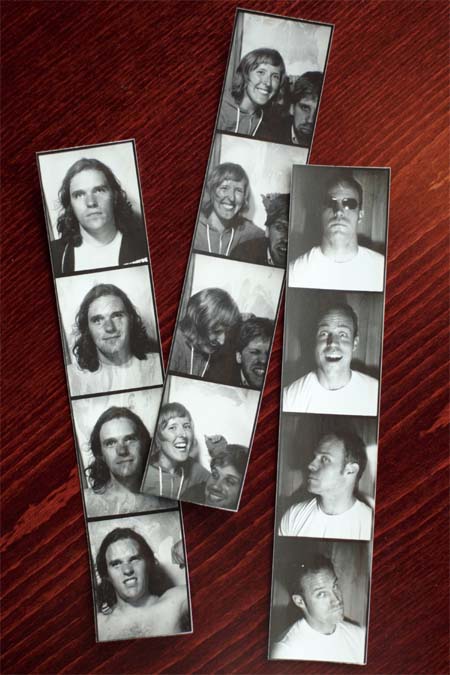

Marc Leibowitz, left, and Jim Johnson a few days before the March 9, 2007, grand opening of The Waiting Room Lounge.

The Waiting Room

The Waiting Room’s origin story goes back well beyond 2007.

Working under the moniker One Percent Productions, Marc Leibowitz and Jim Johnson have booked the best indie shows in Omaha for more than 20 years. Remember that amazing Arcade Fire show in November 2004? It was a One Percent Production. Or that time when Sufjan Stevens played at Sokol Underground with his cheerleader orchestra during his Illinois Tour in September 2005? A One Percent Production. How about when Interpol played at Sokol Underground during a blizzard in January 2005? Again, a One Percent Production.

Those and thousands more shows earned Johnson and Leibowitz the reputation as the best indie rock bookers in the area, playing a pivotal role in exposing an entire generation of future Omaha musicians to the music that would influence their careers.

The duo put on so many shows at Sokol Underground some thought they owned the place, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. “At the time, we just wanted a place of our own,” Leibowitz said. “Sokol Underground was the basement of a 100-year-old building. The shows we were getting at that point couldn’t be in that venue anymore; they deserved something nicer.”

Like Kulbel and Nansel, Leibowitz and Johnson spent years looking for the right location. But unlike the Saddle Creek Records duo, who had visions and resources to spend millions to build their dream club, “we were looking for something very cheap,” Leibowitz said. “That’s why Benson became attractive.”

In 2006, when The Waiting Room project began, Benson’s business district was comprised mostly of thrift stores and empty store fronts, with a few legacy shops still hanging on. “Benson seemed very old, and there were a lot of old businesses,” Leibowitz recalled, “and old-timey bars. We were different.”

Leibowitz said their needed investment to open in Benson was minuscule compared to what it would have cost to go into a new development, like Midtown Crossing. But the gamble was whether they could get people to come to this forgotten district of Omaha.

“We figured if people were willing to come to our shows at Sokol Underground and go down into that basement and deal with what we were dealing with — the neighborhood and the parking — then we were pretty sure if we booked the right shows, they would follow us to wherever the club was, as long as it was centrally located.”

Forcing their hand was the fact that Johnson had just quit his full-time job and Leibowitz had gotten laid off from his. It was ‘Try it now or never try it,'” Leibowitz said.

The financing was straight-forward — the duo used their life savings as collateral to get a loan to cover the balance of the $100,000 needed to remodel what had once been a biker bar called Marnie’s Place, and years before that, the legendary Lifticket Lounge where Nirvana once played.

“It wasn’t turnkey,” Leibowitz said, “but it was turnkey enough that we could go in for a cheap amount of money and make do until we made enough money to fix the place up, build nicer dressing rooms, open the ceiling, buy better air conditioning, buy a better sound system, do all the things that we could have done from the beginning if we would have borrowed all the money we needed, sort of in the style that Slowdown did. That wasn’t a position we were in.”

Instead, those improvements would come over time as The Waiting Room quickly began to build its rep one of the hottest clubs in town shortly after opening on March 9, 2007.

Instead, those improvements would come over time as The Waiting Room quickly began to build its rep one of the hottest clubs in town shortly after opening on March 9, 2007.

“Our dream was to own a club,” Leibowitz said. “Our dream wasn’t to open this club necessarily, but our dream was to have our own spot to do the music that we liked, that we had been doing at Sokol Underground and O’Leaver’s and other people’s places.”

At the same time, One Percent Productions was still very much a going entity. “One Percent Productions rents The Waiting Room for shows, similar to how it would rent Slowdown,” Leibowitz said. “The Waiting Room isn’t the entity taking a risk on shows. If a show loses money, it’s not The Waiting Room’s money. Now, Jim and I own both, so it’s all the same, really, but mentally, it’s different.”

In fact, Leibowitz said, in 2011 when he and Johnson found partners to open Krug Park, a craft beer bar located across the street from The Waiting Room, dollar-for-dollar it made more money than The Waiting Room “because it’s really hard to make money in the music industry.”

“The bar business is a great place to make money, but you have to figure out how to get people to come and drink at your establishment,” Leibowitz said. “For other places, that could be whatever shot special they can come up with. Our way happens to be through live music.”

That means booking shows that draw crowds. Leibowitz said staying relevant in terms of the acts it books is one of their biggest challenges, especially as they get older and music changes. “The music’s not the same in your 40s as it was in your 30s or 20s,” he said.

He also admitted there have been “politics” they’ve had to deal with in that One Percent also booked shows at Slowdown. “That’s been a strain for the eight years we’ve booked at Slowdown, and it’s been a strain for the two years that we really haven’t been doing much booking there,” Leibowitz said. “There is still a small pie that we’re all trying to feed off, and there is still a limited amount of business that can come through Omaha and be successful.”

Leibowitz says booking shows isn’t difficult; booking successful shows is.

“It’s hard to pick which ones are going to be a financial success, because there’s not a lack of shows to be booked, there’s a lack of potentially successful shows to be booked,” he said. “You’re still dealing with the same thing people dealt with 10, 20 or 30 years ago. If something’s not super popular or not on the radio, how are people hearing about it, and how do you get the word out? How do you pick which show to buy?”

At the same time, tickets prices have risen, along with the costs associated with running a live music venue. Agents now have assistants marketing the bands, which means more demands on the venues and local promoters. “There’s a lot more work per show than I think there ever has been,” Leibowitz said.

But the risks involved with booking a show haven’t changed. “I still consider myself a professional gambler,” Leibowitz said. “I”m gambling on every show I buy. There’s no guarantees in this business.”

Leibowitz and Johnson balanced their risks by diversifying their business in the form of real estate. Since opening The Waiting Room, the duo have bought the building that houses the club, as well as the building across the street that houses Krug Park and restaurant Lot 2. They also own the building that houses restaurant Au Courant and are closing on yet another building in the area.

Buying property allows Leibowitz and Johnson to have more control over who comes into the area. “It really does matter what these businesses are,” Leibowitz said. “Getting the right businesses that are going to succeed brings everybody else up.”

There’s little doubt that 10 years after The Waiting Room opened, Benson has evolved into one of the city’s most robust entertainment districts. Those once empty storefronts are now filled with new bars, restaurants and other businesses that may not have taken a gamble on Benson if Leibowitz and Johnson hadn’t.

“Benson is a thriving community and still has a long ways to go,” Johnson said. “There’s a lot that’s changed in 10 years. I think we sparked it and got people to the area, along with (cigar bar) Jake’s and others. Everybody’s had a little piece of it; every little bit that’s opened has helped.”

Yet another property Leibowitz and Johnson purchased houses Reverb Lounge, a new bar and music venue that the duo opened in September 2014, just around the corner from The Waiting Room on Military Ave. The space provides a high-quality venue for shows too small for The Waiting Room.

Despite diversification, The Waiting Room remains Johnson’s and Leibowitz’s first love. And though it’s renowned for the national touring shows One Percent books on its stage, Leibowitz pointed to another factor.

“A good amount of The Waiting Room’s success is because of local music,” he said. “We host a lot of local shows. There’s big support for local music here. People like to see their friends’ bands play.”

From a national booking standpoint, Leibowitz recognizes they need to give the people what they want.

“There’s a lot of shows that you have to do in order to fill your calendar,” Leibowitz said. “We’re in the concession business. We need to get people in to drink, and that’s the ultimate part of running the venue — striking that balance between booking what people want to see and what you want to put on.

“We still buy shows we absolutely know we’re going to lose money on because we think the show’s cool or it’s an artist we really like,” he added. “We’ve got to book the stuff that we really like, or else this business could become a drag.”

So does Leibowitz think The Waiting Room will be around for its 20th anniversary?

“Boy, I hope it’s still around in 10 years. I expect it will be,” he said. “I mean, 10 years from now I’ll be 53. Do I expect to be doing the same role at The Waiting Room that I do now? No, I don’t think I can, but I think it’ll be there.”

* * *

Tomorrow: Pt. 2 — Leibowitz, Johnson, Nansel, Kulbel and your fearless reporter talk about our favorite shows at The Slowdown and The Waiting Room over the past 10 years…

* * *

Read Tim McMahan’s blog daily at Lazy-i.com — an online music magazine that includes feature interviews, reviews and news. The focus is on the national indie music scene with a special emphasis on the best original bands in the Omaha area. Copyright © 2017 Tim McMahan. All rights reserved.

Instead, those improvements would come over time as The Waiting Room quickly began to build its rep one of the hottest clubs in town shortly after opening on March 9, 2007.

Instead, those improvements would come over time as The Waiting Room quickly began to build its rep one of the hottest clubs in town shortly after opening on March 9, 2007.

Recent Comments